My father died last week.

Yesterday afternoon I had that familiar impulse to call him, followed by the recognition he would not answer. I had seen him twice during the week before his death, and both times I peppered him with questions.

At the end of the first visit, my dear husband and I helped my father into bed, and then Paul left us alone. I kneeled to look into my father’s eyes and said,

“I just want to make sure you’re OK, Dad.”

He gave me a strong, searching look, and responded,

“I just want to make sure you’re OK.”

I kissed him and assured him I was much more than OK; I was blessed and grateful for all he had done for me, for us, and for the world.

Four days later, I returned to take him to lunch. Concerned that he was unhappy in this nursing unit, I asked if he would rather come live with me, if our home could accommodate him. He said no. Then I asked if he would rather live with my sister Deb, if her home were made ready. He said no. Then I asked if my sister Kate’s new home might be better. Again, he said no.

Then I asked him if he had anything he wanted to say to me, and he said yes. And he paused. The pause lengthened. His dear friend Anne came back to the lunch table, and the conversation turned to general topics.

After lunch, I pushed him into the sun, guiding his wheelchair along the sidewalk to his room. We enjoyed the warm, fresh air on our arms and faces. He had not bitten into his roast beef sandwich, and he was subdued. I reminded him there was something he wanted to tell me, and asked if he remembered. He thought for a moment, and said, “I forgot.”

Then I asked him what he wanted and needed. He answered, “Attention.”

I told him that my brother Jim was going to be there the following day, and he brightened up. Late that evening, I shared his request with my siblings, and niece Kathleen, via email. That was Wednesday night, September 7th. On Thursday afternoon, we convened by his bedside. Thursday morning, I had baked an apple pie to bring to the gathering. My sister Kate fed it to him, with the requisite vanilla ice cream. We surrounded my father with gratitude and love. For the next four nights and days, at least one of us was in his room, by his side at every moment. My sister-in-law Natalya drove up from Silver Spring Maryland twice, with her car filled with his grandchildren. On the fifth morning, after my sister Deb left the room, her husband Pierre witnessed my father’s final breath.

During and after the hours I was with him and he was beyond words, I read his oral history. My sister Deb recorded and painstakingly transcribed it years earlier. The conversation wanders and winds back on itself. Given the task of “finishing it” in 2009, I couldn’t do it. But I compiled the rough transcripts into one meandering document and performed a light edit. As my father lay dying, I dove back into the conversation, glad to have these stories and fragments to prepare his tribute.

I spent the better part of four days reading, writing and researching facts for his obituary, and then I sent the draft to my siblings, as agreed. Although we share his love, we each have a unique view of who he was and how he lived. I cut the article down for size, and sent it off to my father’s favorite newspaper: The Philadelphia Inquirer. It ran on Sunday, September 18th, and you can read the published version by clicking this link.

Here, below is the uncut version of my personal tribute.

It includes his statement about the value of obstacles and his pride in his mother’s kitchen garden.

He inspired me with his life, and now in death he continues to inspire. I am blessed and grateful.

I hope you enjoy this story, which offers a glimpse into the complex man I called “Dad.”

Blessings,

Harold Frederick Wilson, 94, passed away peacefully on September 12, 2016 in Blue Bell, PA. He was surrounded by family for his final days, and had celebrated his recent birthday with even more family who traveled from far and near.

A member of the “Greatest Generation,” he was born August 15, 1922 to Erma Rebecca Frederick and Lloyd Ralph Wilson in Columbiana, Ohio and he became the first in his family to graduate from college (Oberlin, ’44), and earn a Ph.D. in organic chemistry (University of Rochester, ‘50). This led to his stellar 33-year career beginning as a lab head and progressing to Vice President and Director of Research at Rohm & Haas, where he published numerous scientific papers and held 30 patents. He and his teams developed processes and compounds that increased food production internationally.

He was a great believer in education and self-development. When asked what led to his success, he said there were two reasons, “I was treated with a great deal of love by my mother. She nurtured me and I grew up feeling that I was going to college . . . I had a counter balance to that, and that was stuttering.” Although his stutter never completely disappeared, he became a respected corporate and financial leader, serving on many international boards. His deep baritone voice was so resonant and strong that his whisper could be heard across a room; his sneezes frightened small children.

Fred met Alice Margery Steer at Oberlin College. They married in 1949 and raised four children, then welcomed ten grandchildren into their hearts. Since Alice’s death in 2001, he delighted in embracing nine great-grandchildren into the family.

A man of few words, Fred was a voracious reader and lifelong student of business, bridge, public and international affairs, and the financial markets. He loved being part of a community, from his childhood in Columbiana, where his father served as village clerk and their telephone number (68W) was a party line that rang both at home and in city hall. He and Alice started their family in Moorestown, New Jersey in the 1950s, where he became one of the founding developers of Sunnybrook Swim Club. From the 1970s through the 1990s, they actively supported the renaissance of their summer home, Cape May, New Jersey. They also played vital roles in Merchantville, New Jersey, where they lived between 1990 and 2002.

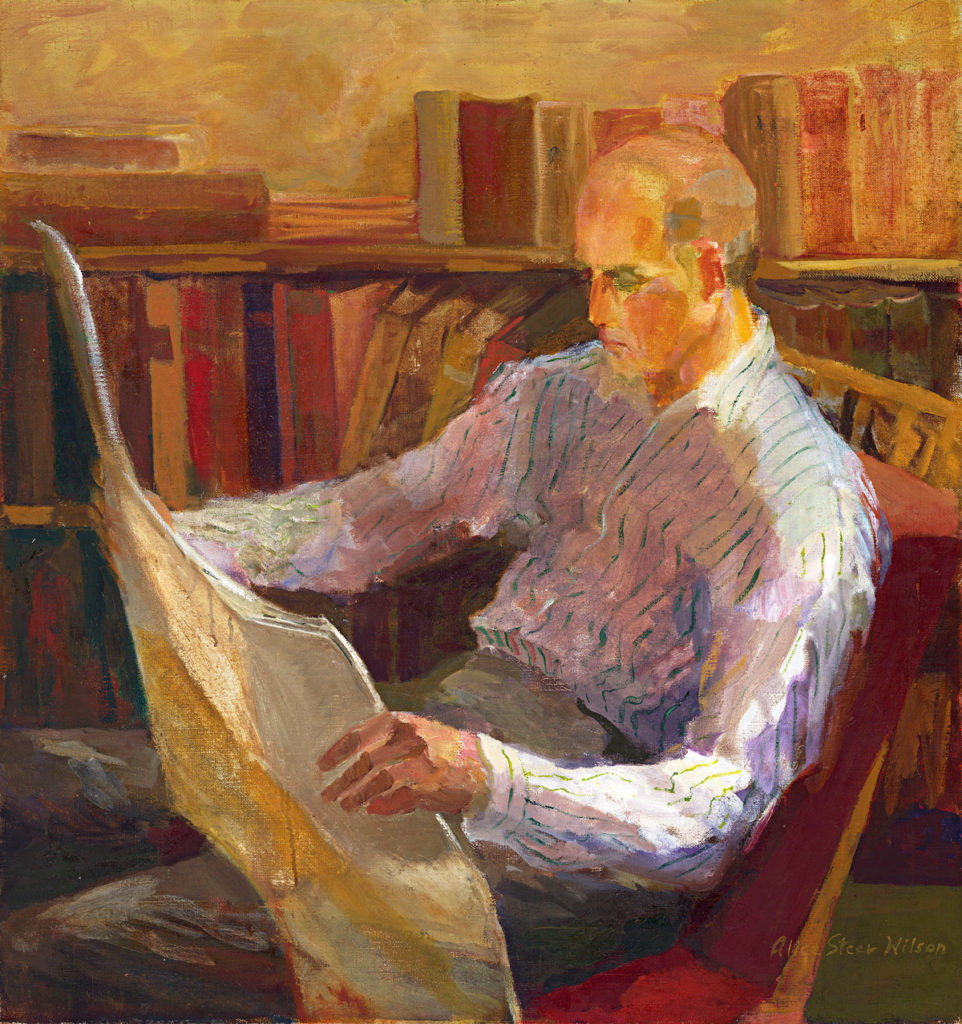

When retired, his wife asked him to critique her paintings; he was baffled by the request. With no formal art training, and a scientist’s devotion to finding flaws, he knew he could get into trouble. He asked how to proceed. She requested first impressions only: what drew his interest, and what distracted. He provided that and more by becoming a partner in her craft and helping her negotiate with printers, distributing her Cape May note cards to merchants, and serving as her most frequent, unpaid model while he read his always in-hand newspaper. It was Fred’s idea to increase production quantity of the note cards, to make them more widely accessible to buyers. Alice agreed, and became the quintessential Cape May painter whose work remains beloved today. By 1997, when they celebrated their 20th year of the card business, they had sold more than 1 million Cape May notecards.

Fred’s WWII service as lieutenant in the Army Air Corps included close calls, not always in the line of duty. While on leave in St. Moritz, February 1946, he and a fellow GI were taking ski lessons and they were recruited to a bobsled competition by a racer name Milo. Always game, they stepped up to a harrowing but triumphant set of runs. Later, they were told “Milo couldn’t get Swiss to go with him because they didn’t like the way he steered and they didn’t want to go over the edge. That’s why he had to get Americans.” Fred applied the brake only one of the four times Milo told him to, thus they got down the hill in record speed and won fourth place.

He memorialized his most dangerous stint as co-pilot of a glider that flew across enemy lines near the end of the war, in a letter he wrote home to reassure his mother and siblings that he survived. He reported that they landed perfectly but were pinned by sniper fire, and “that was when I learned to dig a hole and sit in it at the same time.”

His ability to dig holes and make camp was one of the pleasures he was determined to share with his wife and children. In the 1960s he led annual family road-trips in a Chevy wagon loaded with four kids and a homemade rooftop footlocker, co-piloted by Alice. He shared his love of hiking, canoeing and exploring the country’s state and national parks from North Carolina to Maine, Pennsylvania to Wyoming.

Travel became a passion, fed by his time in France during WWII, then by numerous international business trips. Although he became a connoisseur of fine food and wine, his early love of fresh local produce and home-baked pie never left him. It was his mother’s backyard garden in Columbiana where he gained respect for agriculture and working with the elements to produce abundant food. He told his daughter Deb, in an oral history she recorded 2009, that his mother’s kitchen garden yielded “rhubarb, asparagus, raspberries but we would normally grow corn, beans, potatoes, lettuce, radishes, onions, cabbage and parsnips. We buried it in leaves to keep all winter, and had a sour cherry tree, and grapes back near the chickens. When I was a teenager it was my job to spade the garden in the spring. I also took care of much of the garden. Mom was the main overseer.”

Fred is survived by his large and loving family, including his four children and their spouses: Janice Wilson Stridick and husband Paul, of Merchantville, NJ; Deborah Eastwood Ravaçon and husband Pierre, of Ft. Washington, PA; James Frederick Wilson and wife Natalya, of Silver Spring, MD; and Kate McConaghay Frederick and husband Sam, of Lancaster, PA. He was thrilled to swell the ranks of great-grandchildren to nine over the past decade as a beloved and doting grandfather/great-grandfather to Sean (Kim / Jack, Elias) and Josh (Lindy / Will, Daniel) McConaghay, Kathleen (Mauricio) Eastwood Diaz, Jake Eastwood, Vatslav (Christina / Christian), Hariton, Anfisa and Pasha Alice Wilson, and Elise (Josh / Ella, Felix) Ravaçon-Cohen and Aimee (Johan / Alex, Leah) Ravaçon -Grip.

Friends and family are invited to attend a memorial service at the Normandy Farms Estates, Blue Bell, PA, at 2pm, Saturday, October 22nd, 2016. Donations in his memory may be sent to the Mid-Atlantic Center for the Arts & Humanities (MAC) PO Box 340, Cape May NJ 08204, or The Chemical Heritage Foundation, https://www.chemheritage.org/give.

Oil by Alice Steer Wilson

Thank you for capturing the whole man

His memory will always be for blessing

Shalom,,my

Dear cousin